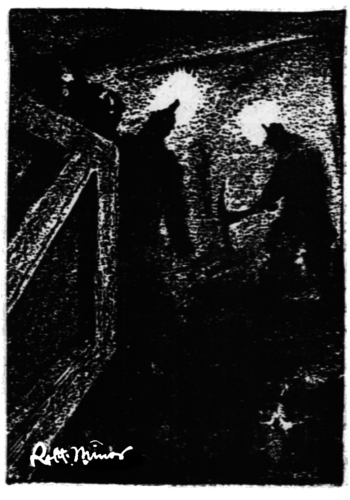

OF THE MINES

Among all the superstitions that haunt the souls of men there are none more firmly established than those which develop among the men who toil in the dampness of the mine, declares the Butte (Mont.) correspondent of the Philadelphia Record. And of all superstitions there are none more weird than those of the “graveyard” shift. The “graveyard” shift is the dead of night—usually between 11 p. m. and 3 a. m.—and it is then that the “tommy-knockers” are most often heard. Nearly all of the big mines of the west are in operation constantly during the 24 hours of every day and the seven days of every week. A great mining plant does not shut down on the Fourth of July or even Christmas. The men are driving the drills, the “shots” are being fired, the broken ore shoveled into cars and carried out through the shaft or tunnel, and the big mills are grinding, pounding and roaring for 365 days in the year. The miner who works steadily has no variation in his life. He is as far away from the world as the sailor at sea, and the conditions are far more propitious for the birth and growth of superstitions.

Suddenly, in the never-ceasing drip, drip of the water, he hears some sound—the reenter ring of a hammer not far from him. He is puzzled, for he knows that he is alone in that part of the mine. Never doubting the accuracy of his